If it were not for the worldwide success that Rashomon gained only after The Idiot was released, the films that followed for Kurosawa might have been very different, if he even got to make any at all.

The Idiot, based on the novel of the same name by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, was neither a financial nor critical success.

In his childhood, Kurosawa was exposed to large amounts of foreign literature and films. This is how Kurosawa became acquainted with Dostoyevsky.

Dostoyevsky would remain Kurosawa's favorite author. It was because of his love of Dostoyevsky that Kurosawa would make The Idiot, and it was ultimately the reason why the film failed.

The original cut of the film that Kurosawa did was over four hours long. The studio, Shochiku, cut the film down to 166 minutes against Kurosawa's wishes.

The original cut has been lost.

Needless to say, Kurosawa was devastated by the failure of The Idiot, a film that he poured every ounce of effort and love in to.

Luckily Kurosawa was saved by the success of Rashomon. After The Idiot Kurosawa would go on to make some of the best films of his career.

He would never again direct a film based on material by Dostoyevsky, but he would direct two other films based on Russian source material. These films would be 1957's The Lower Depths and 1975's Dersu Uzala.

Story:

Kurosawa's version of The Idiot is set not in Russia but in Japan shortly after the end of World War II.

The film is broken up into two parts. The first part, entitled "Love and Agony", begins with two men traveling back to Hokkaido, Japan.

Kameda (Masayuki Mori) tells one of his fellow passengers that he is returning from a U.S. Military hospital where he was being held due to "idiocy". Kameda was diagnosed with epileptic dimentia, a mental illness that makes Kameda very childlike.

Kameda tells the man, Akama (Toshiro Mifune), that he was facing a firing squad but was released at the last minute when they realised they had the wrong man.

Akama says he is returning to claim his dead father's fortune and marry a women named Taeko Nasu.

The two men discover that Nasu is actually engaged to a man named Kayama (Minoru Chiaki). At her own birthday party Nasu rejects Kayama after speaking with Kameda.

Kameda tells her to come stay with him, but she rejects him as well, fearing she will tarnish his pure soul. Instead, she goes with Akama and dangles the prospect of marriage in front of him, but never actually marries him.

After discovering Nasu still has feelings for Kameda, Akama attempts to kill him.

In part two, entitled "Love and Loathing", Kameda begins a relationship with another young girl named Ayako.

Before they marry, however, Ayako wants to confront Nasu. The meeting does not go well. Ayako runs away with Kameda in pursuit, and Nasu falls to the floor where she is eventually killed by Akama.

Kameda returns to Akama who is now seemingly suffered the same fate as himself.

Analysis:

The winter landscape in The Idiot looks as much like Dostoevsky's Russia as it does Kurosawa's Japan.

Examples of both Russian and other foreign influences can be found throughout the film.

The Russian song "Night on Bald Mountain" can be heard during the ice carnival scene, and the famous Norwegian song "In the Hall of the Mountain King" can be heard at another point in the film.

Clearly Kurosawa was trying to find a balance between his own country and the country in which the source material was set.

It is far more apparent in part one of the film that it was edited by the studio. The plot moves frantically and the editing often seems jumpy and erratic.

Part one of the film also contains title cards that essentially tell the story without showing anything. These cards also give some information about the background of the story, specifically about what Dostoevsky wanted to show in the story.

These cards might have been placed simply to give confused audiences a bit of an explanation of the story, or they simply may have served as easy ways to advance the plot and cut time from the finished film.

These titles disappear later into the first part and are not present at all during the second part.

One of the titles during the first part describes Dostoevsky's intentions for the "idiot" character Kameda.

The title card says that Dostoevsky wanted the Kameda character to be a pure soul, so he made him an "idiot".

Although Kameda can be quite socially awkward at times, he is hardly incapable of functioning in modern society.

Kameda might be likened to someone from the past coming into the present. While they might be unaware of contemporary society norms and intricacies, they would no doubt still be able function.

Throughout the film Kameda is both ridiculed and almost sanctified because of his illness.

People often call him an idiot or similar names. They often talk to him as if he were not in the same room. They make fun of him or scold him when he innocently breaks a rule they believe is common knowledge, like when he buys red carnations that, unbeknowst to him, symbolize love.

On the other hand he is often praised as well. Akama on several occasions calls him a lamb, and Nasu refuses to marry him because she does not want to tarnish his innocence.

Visually The Idiot contains only a few memorable shots. The first comes when Kameda and Akama first get to Hokkaido. Shot in almost newsreel like fashion and most likely with a long lens, Kurosawa shows us a montage of the snow-covered Japanese city.

The shots work perfectly to establish the setting and to place the audience in the world of the film.

The two other sequences are quite similar. Kurosawa uses several close-up shots to capture the extremely emotional confrontations during two separate parts of the film.

The first occurs when Nasu arrives at Kayama's house and meets his family.

The second is when Ayako confronts Nasu. Nasu tells Kameda to choose between them and a standoff begins. The sequence is made that much more powerful by the frighteningly intense expression on Nasu's (Setsuko Hara) face.

The film is, in the end, far more character driven than plot driven. Despite the petty romantic quarrels that surround the film, at its core is the story of how one innocent man is corrupted by society.

In the end everyone by Kameda seems like the crazy ones. Ayako says it perfectly in her final speech, almost pleading with the audience when she says, "If only we could all love as he did." She then calls herself the idiot.

The film is one of the darkest for Kurosawa, not only because of its subject matter but also in terms of its photography.

Akama's house is incredibly dark, reflecting his personality. Kameda even tells him this when he comes to visit. Kameda frequently calls people out and speaks frankly about them.

In Akama he sees darkness; in Nasu he sees a great deal of pain. What he sees in Nasu contributes greatly to Kameda's love for her.

Kameda tells Ayako that he often wants to take the place of a person in pain.

But by the end it seems that even Nasu is beyond recovery. She drapes herself in black, looking almost like Death himself.

The subject matter was perfect for a director with the sensibilities of Kurosawa. His humanist attitudes most certainly influenced this film.

Throughout his films there seems to be an overwhelming love for those who are rejected or looked down upon in society. As a child Kurosawa himself was thought to be a bit slow.

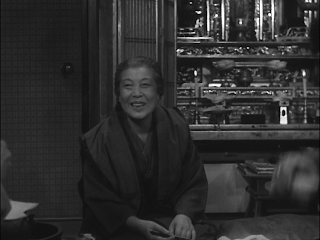

In The Idiot these feelings not only manifest themselves in the form of Kameda, but also of Akama's elderly mother. His mother prays quietly and serves the men tea. Not surprisingly, she takes a liking to Kameda. She smiles sweetly, never saying a word, and watches as the men eat the cake offering she has prepared.

They say Dostoevsky does not translate well to the screen, but if one person could do it, it would and should have been Kurosawa.

It is an incredibly powerful film that, like many of Kurosawa's, is very reflective of the present despite its age.

It is a shame the original cut of the film is not lost, otherwise what is now considered a lesser masterpiece in the Kurosawa repertoire might have ended up a first-rate masterpiece.