Despite the failure of The Idiot, after Rashomon began winning awards Kurosawa began to receive new offers to direct films.

For Ikiru, Kurosawa would return to Toho once again. The film, according to its opening credits, was selected as an arts festival selection in 1952.

While many of Kurosawa's films focus on either a single individual or small group of individuals, each one makes a larger universal statement.

Rashomon takes on the human propensity to embellish, The Hidden Fortress deals with friendship and loyalty, and The Bad Sleep Well makes a statement about bureaucratic greed.

Ikiru is a film that focuses on one of the most universal of themes, death.

In fact the film, Kurosawa says, was born out of his own thoughts about death. Thoughts that would resurface a few decades later when Kurosawa attempted suicide.

Story:

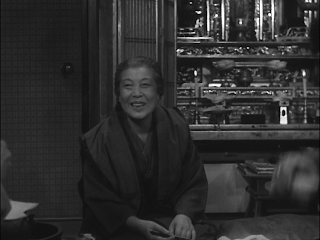

Ikiru (meaning "to live") revolves around one man, Kanji Watanabe. Watanabe is played by Takashi Shimura in his best and most central role ever in a Kurosawa film.

Watanabe works as the chief of a public affairs office, one of the many branches of a bureaucratic system that we soon realize is incredibly flawed.

While Watanabe toils away, a local women's group comes in to demand a park be made over a cesspool that they claim is making their children sick. Watanabe and the other's give these women the runaround, and they are not seen again until much later in the film.

Watanabe is a seasoned bureaucrat. He has worked without a sick day for over 30 years, a fact his fellow employees are quick to point out when he misses several days of work.

What those employees don't know is that Watanabe has visited the doctor. The doctor tells him he has a minor ulcer, but another patient at the hospital tells Watanabe that this is merely a nice way of telling him that he has stomach cancer.

The news leaves Watanabe devastated. Watanabe, seeking to finally live a little before he dies, happens upon a writer who spends the night with him wandering about the Tokyo night life. Watanabe's fun lasts only a night, the next day he is still as grief stricken as the day before.

With a son and daughter-in-law who don't seem to care about his odd behavior and without anyone else to turn to, Watanabe latches on to a young girl who quits the public affairs office. In her he sees life.

After realizing that he can actually make a difference and do something with his life before he dies, Watanabe commits himself completely to building the park the women were demanding at the beginning of the film.

The rest of the film is told at Watanabe's wake. There the guests tell the rest of the story, trying to figure out exactly what Watanabe's motives were, and who was really responsible for building the park.

After several cups of alcohol, the men commit themselves to living as Watanabe did in his final months.

But as the end of the film shows, a deeply flawed bureaucratic system is not easy to break, and life goes on as it did in the beginning.

Analysis:

Unlike Kurosawa's period films that are more subtly critical of modern Japanese life, his modern day pictures almost always have something to say about the ills of society.

Ikiru is no different. The film is, perhaps with the exception of The Bad Sleep Well, the most wholly critical in that it not only makes a comment on society as a whole, but of human beings in general.

Kurosawa was clearly living in a society that he saw as complacent. The characters in the film talk about the flawed society that they live in, but they are seemingly helpless or too lazy to do anything about it. This is where Watanabe comes in. Watanabe represents the complacent Japanese everyman.

The beginning of the film is marked by narration. In an incredibly smart move by Kurosawa, the narrator brings us into the film world and explains the kind of person Watanabe is.

"He is simply passing time without living his life," the narrator says.

We are told from the beginning that Watanabe has his stomach cancer, and are almost encouraged to make judgments on Watanabe even before we have gotten to know his character. It is because of this that we can more fully appreciate what he does later in the film.

After Kurosawa introduces us to Watanabe, he brings in the problem that he will eventually solve, and raises a societal issue at the same time.

When the group of women come into the public affairs office to see about filling in a cesspool they say is making their children sick, the public affairs clerk tells them to go to the engineering department where they are told to go another section. This game continues until they end up at the same place they started, Watanabe's department.

The women are finally told to simply put their complaint in writing, but are never told that it will be looked at or responded to.

Even at this early stage it is clear that little if anything gets done in this system. Nobody, including the main character, is willing to step in and change anything, and everyone is seemingly content with keeping the system the way it is.

After this the film turns sharply towards the individual instead of the bigger problem. From here we follow Watanabe.

Kurosawa does not often focus on family dynamics. With the exception of 1955's I Live in Fear, the modern Japanese family never really held much importance for Kurosawa. The family was more the domain of Yasujiro Ozu, perhaps most memorably in his film Tokyo Story.

In Ikiru, Watanabe lives with his son Mitsuo and his wife Tatsu. Far from the traditional Japanese children who respect their parents and care for them in their old age, the two are far more interested in themselves and their own lives rather than whatever their father is going through.

They are the new Japanese couple. In pure capitalist fashion their only goals in life are to accumulate wealth, move into a modern home and shed their Japanese traditions. It is only until after their father dies that they realize the error of their ways.

When Watanabe does eventually learn of his impending death, he is totally consumed by it. In a brilliantly filmed sequence, Watanabe walks out of the doctors office and out onto the busy street. Despite all the traffic there is silence on the soundtrack. We are hearing what Watanabe is hearing. He is so utterly consumed by the news he has just received that he is oblivious to his senses. Finally, when he walks out into the street he snaps out of his dream-like state and the soundtrack is flooded with the loud noises of the busy street.

Even though Watanabe admits he is afraid of death, he can think of nothing to do when he is alive.

The writer he meets says it all when he says, "human beings only realize how beautiful life is until they are about to die."

It is only when Watanabe is nearing death that he seeks out new ways to live. Watanabe begins to reinvent himself. He buys a new hat to match his new self. He goes to clubs and dances and drinks to his hearts content. Even during this sequence it is clear the nightlife has little effect on Watanabe's emotional state.

In the most memorable scene of the film Watanabe requests an old song called "Life is Brief" to be played in a dance hall. When the slow song begins Watanabe starts to sing along. His voice causes the others in the room to stop and stare. It is the voice of a dying man. Kurosawa enhances the scene by showing Watanabe's face in close-up.

By the next morning it is clear that he is no more alive than he was the day before.

He then sees new life in the form of the youthful Toyo. With her he laughs and plays games. But this doesn't last forever. Toyo begins to get uncomfortable with an increasingly distraught Watanabe.

Finally he commits himself to building the park. Through this one final act he will live. For him, living is simply doing something out of the ordinary with your life. By breaking from the norm, he is insuring that his life is not going to waste.

Watanabe is not a particularly strong willed character. In several flashbacks he is shown as more of a coward than anything. One example being a flashback of a baseball game where at one moment he is prepared to boast about his son's hit and the next is sinking into his seat with shame over a botched attempt at taking second base.

But Kurosawa shows us that when we do live to the fullest and are determined enough, we can redeem ourselves.

In a series of flashbacks at the wake, we see Watanabe defying adversity and standing up for his cause at every turn.

He confronts the system by taking on the other section chiefs.

He stands face to face with angry businessmen who feel threatened by him.

He stands face to face with angry businessmen who feel threatened by him. He even faces the deputy mayor and openly questions his decision to reject the park proposal.

He even faces the deputy mayor and openly questions his decision to reject the park proposal.

In the end Kurosawa seems to see people as essentially ignorant, and that unless they are either facing death or incredibly drunk, they will never admit to themselves that their lives are mundane and that they essentially dead.

This is exemplified not only by Watanabe's journey from lifeless bureaucrat, but also by the guests at his wake.

One man at the wake defies the others by insisting it was through Watanabe's efforts alone that the park was made. The others believe other factors were to blame, whether it be restaurant owners seeking new land for shops or city officials hoping to be re-elected. It is only when they become drunk that they admit the truth and swear to remember what Watanabe has done.

But slipping into the background is the man who initially spoke up for Watanabe, not having touched a drink he kneels in front of Watanabe's portrait and swears an oath himself.

The audience is certainly asked to relate and sympathize with this man. He most closely resembles what the audience should be feeling and how they should be reacting. We have seen the story from start to finish and know that Watanabe is solely responsible for the park.

The film attempts to end on a light note by showing the fruits of Watanabe's efforts when we see the children playing in the new park.

But it is the scene before this that is more crucial to the film. One of the men at the wake has taken over Watanabe's position.

But it is the scene before this that is more crucial to the film. One of the men at the wake has taken over Watanabe's position.When a new proposal comes his way he merely passes it off to another section. The sober man from the wake stands up in defiance, but realizing the whole rest of the room is not with him, slowly sits back down.

It is not through the efforts of one man that the society will change, Kurosawa teaches us, but perhaps with enough people change can come.

More than any other film, Ikiru implores its viewing audience to reevaluate their lives. It asks them to decide if they will continue to live day after day doing the same thing simply to keep the status quo, or if they will act as Watanabe did and make something out of their lives.

While many issues addressed in the film relate more to the time it was made, the universal themes of life and death resonate even today.